For Stephen Durand, March 16, 2018, began like most other daysāwith an inordinate amount of squawking. Durand lives on the Caribbean island of Dominica and oversaw the federal aviary that houses rescued parrots, including casualties of Hurricane Maria. Six months earlier, the storm had leveled large numbers of the islandās trees and stripped many more of their fruit and foliage, threatening two endemic parrot species.

The festive green Red-necked Parrot, or Jaco, and the monkish, mountain-dwelling Imperial Parrot are a source of pride for Dominicans. When their populations were at an all-time low in the 1980s, Durand helped launch an amnesty program to reclaim pet parrots for research and education. After the hurricane, he hosted International Fund for Animal Welfare veterinarians who performed surgeries under generator-powered lights. āGoal is to RELEASE back home to their wild habitat!ā they wrote on Twitter that February. Four Jacos were set free and aviary staff tended to those still recuperating.

In March Permanent Secretary of Agriculture Reginald Thomas sent a memo to Durandās boss: āNone of the birds being housed at the facility should be released into the wild until further notice.ā Durand had an inkling of what this was about. For years heād been concerned about a group of deep-pocketed European parrot enthusiasts cozying up to island leadership, promising to build capacity āat a local level to better manage the islandās resources,ā as they wrote in a 2012 letter. Durand was skeptical. āI had been trying to avoid these people for a long time,ā he says.

Led by a German named Martin Gerhard Guth, the Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots (ACTP) bills itself as a nonprofit dedicated to protecting endangered parrots and their habitats. Since its founding in 2006, countries, institutions, and people across the Americas have handed over rare birds to ACTP for captive breeding to rebuild populationsāincluding Caribbean Amazons and ³§±č¾±³ęās Macaws, which are extinct in the wild. The organization operates a licensed zoo in Germany, and birds are also kept in the personal aviaries of ACTPās members, who pay $1,100 to join. Surplus parrots that members and zoos donāt want are traded or sold to outside breeders. One ACTP representative, for instance, sells Hyacinth Macaw chicks at his pet shop that can go for around $18,000 apiece. How many birds are bred versus collected or sold nobody knows, because ACTP does not publicly disclose its finances or structure.

When Durand left work that Friday, he told the staff heād be attending a funeral the next day. After services, Durand got alarming news: The parrots were gone. Several Germans, accompanied by the agriculture minister, extracted the 12 healthiest specimens. The birds were flown to ACTPās invitation-only zoo outside of Berlināa place that so zealously guards its flock that visitors arenāt allowed to take photos without permission.

āRare endangered parrots illegally smuggled from Dominica,ā blared one headline. Both Jacos and Imperial Parrots are regulated under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), but Thomasāa political appointeeāapproved the export permits without the sign-off from Dominican CITES authorities. Paul Reillo, president of the Florida-based Rare Species Conservatory Foundation, co-organized dozens of conservationists, including ±¬ĮĻ¹«Éēās international director, Matthew Jeffery, to demand the parrotsā return. āThere is a long history of rare Amazon parrots being taken from the Eastern Caribbean to Europe for captive breeding, with the expectation that their progeny will be released,ā they wrote in an open letter. āNone of these efforts have born[e] fruit.ā

Itās no surprise conservationistsā hackles were raised: ACTP has been astoundingly successful at acquiring birds. In 15 years, Guth has helped his 18 breeder members obtain near-monopolies on the worldās rarest parrots. While the group says it breeds these birds for reintroduction efforts, not one offspring has ever been released into the wild and only a small fraction have ever been returned to their countries of origin. The group appears to have abandoned entirely its conservation plans in Mexico, after ACTP members got their hands on the endangered parrots they wanted there. Through ACTP, Guth and his members had effectively created a back channel for trading and breeding endangered parrots within the bounds of increasingly restrictive wildlife laws. And conservation goals, it seemed, had become an afterthought designed to put a sheen of legitimacy on the operation.

Or thatās what I deduced, because Guth wasnāt talking. I contacted him about visiting ACTPās zoo in March 2019, but he proved flighty and mercurial. After six weeks of email exchanges, he asked me to confirm dates, then quashed the plan. āI am a [sic] easy person,ā he wrote. āBut your questions indicate a directionā¦ So we stay secretive!ā

Last summer, when Iād lost hope of an interview, Guth invited me for coffee at the Four Seasons in Beverly Hills, where heād come for a wedding. A big, bald man with a brusque manner, he burst into the marble lobby and barked our drink orders in his thick German accent. Taking a seat on the patio, he asked bluntly who else I planned to interview. Guth felt like heād been unfairly smeared before. His wasnāt the first zoo to support its activities by selling endangered animals, he pointed out. If he wanted to, he said, he could throw his parrots on a barbecueāor do anything he likes, short of personally profiting from them.

The conservation world has always had iconoclasts, some of whom succeed spectacularly. One of Guthās efforts has, in fact, finally begun to bear fruit. This spring he made history when he sent 52 captive-born ³§±č¾±³ęās Macaws to Brazil in preparation for their eventual release. Others had been working on this effort for three decades, but Guth was going to bring it to the finish line. And, he hoped, finally silence his critics.

Guthās childhood memories are of an unabiding grayness. The overcast sky, the drab landscape, life itself under the Communist regime of East Germany. Born in August 1970, Guth grew up in Staaken, a town cleaved in two by the Berlin Wall. Parrots were a gaudy missive from the free world.

Guth recalled coming close enough to a caged macaw to get a whiff of its sunflower seed breath, a scent-memory that still moves him. At the age of 10, he obtained a budgie. He became infatuated with color mutants like a sickly yellow Monk Parakeet that he got from a neighbor, and later sold for 3,000 East German Ostmark, according to a blog post by a visiting breeder. That bounty, worth more than $500 today, funded cockatiels, canaries, and parakeets that Guth kept in his familyās barn.

Germans have always had a fondness for exotics. The country is home to some of Europeās earliest zoos, and, during World War II, the Nazis exempted the Berlin Zoo from belt-tightening. When that zoo was walled off during the Cold War, East Germany built its own, which had greater attendance than the nationās top soccer league. Today Germany has more than 400 zoos, nearly on par with the United States, which has four times the population. It also boasts both the worldās largest pet store and the worldās largest aviaries. The worldās most famous parrot parkāLoro Parque in the Canary Islands with 350 species and subspeciesāwas founded by a German.

Guth left school in 10th grade and became an apprentice at a dairy farm, recoiling as he trimmed manure-crusted hooves. In 1989, he hopped a train to communist Hungary. From there he slipped into Austria and made his way to Hamburg in West Germany. He was trudging to a ship in the harbor that served as a floating camp for East Germans when he passed a pet store and peeked inside. The owner hired Guth as the head birdkeeper, and he performed his duties with a Red-and-green Macaw named Kojack on his shoulder.

After the wall fell that November, Guth worked in the construction business and as a nightclub bouncer, but, mostly, he ran a protection racket with a team of heavies under his command and a smoldering cigar hanging from his mouth. According to a court judgment obtained by Lisa Cox and Philip Oltermann of The Guardian, Guth warned the owner of a disco that ābad guys with chain saws and axesā could ravage the place. To another man he offered the coded threat that āwives were unprotected.ā In 1992 Guth helped a drink distributor track down someone who had defrauded him. A half dozen men nabbed the culprit inside a restaurant. Guth held up his cigar cutter and threatened to cut off the manās fingers one by one if he didnāt pay up.

Guthās career choice eventually caught up with him. He spent two and a half years in prison in the late 1990s after being convicted of attempted fraud, predatory and attempted extortion, and hostage-taking. āI have no problems with my past,ā he wrote me in April 2019. āItās part of life.ā

This frank view didnāt hold for long. Later Guth told me that, under German law, his past crimes should not have been reported by The Guardian; when I went looking for the same records at a German courthouse, they werenāt there. Guth had received a certificate of good conduct for staying out of legal trouble in the years since, he saidāproof heād moved on. But his past seemed relevant to people in parrot circles today. Many I contacted were reluctant to speak freely about him; several refused to go on record. āI promised him I wonāt take his name in my mouth again,ā says Robert Peters, a breeder in Bavaria who wouldnāt go into detail about his conflict with Guth. Adds another: āI underestimated his abilities and itās one of the worst mistakes I made in my life.ā And a third: āI fear for my safety and my familyās safety.ā

Guth may have pure intentions when it comes to protecting parrots. And when we met, I did detect some morsel of sincerity beneath his bluster, a belief that conservation can pay for itselfāand that the ends, when it comes to his beloved birds, justify the means.

Parrots are among the most threatened birds. Nearly half are declining in number, and almost one-third face extinction. Deforestation, fueled by agriculture and development, has wiped out wide swaths of their habitat. For nearly a half-century, birds have also been plucked from the wild to feed a thriving pet trade, with hundreds of thousands sold across borders at its peak.

To stem the trade, governments began enforcing existing laws and enacting new ones. The CITES permit system came into force in 1975, allowing countries to track and limit the movements of endangered animals, including parrots. In the 1980s Australia banned the export of all its native fauna for commercial purposes, and the United States and Europe enacted measures that reduced wild bird importation. Such regulations helped reduce poaching of South American parrot chicks from their nests by almost 60 percent, based on data gathered between 1979 and 1999.

Even with such measures, parrots, many of which reproduce slowly, remained dangerously depleted in the wild. Conservationists turned their attention toward captive breeding. The approach, they thought, might be key to reversing the parrotsā plight: build up populations in controlled confines, then release healthy flocks into the wild.

In the late 1970s, the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust launched a program with nine wild-caught St. Lucia Parrots at the Jersey Zoo in the English Channel. It hoped to produce 10 chicks per year; it hatched only 20 over the course of 20 years. Meanwhile, St. Luciaās wild parrot population grew from perhaps 100 individuals to more than 350, thanks to habitat conservation. The lackluster results with St. Lucia Parrots arenāt unique. Back then two-thirds of captive-breeding efforts with threatened species were failing to even release birds.

Captive breeding is so expensive, slow, and risky that itās now widely viewed as a strategy of last resortāto be used in the event of a disease, natural disaster, or another imminent threat. Thomas White works at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serviceās Puerto Rican Parrot Recovery Program, a captive-breeding program that costs almost $1 million per year to run. He says that when done at all, captive breeding should occur within a birdās historic range: Housing species from multiple countries in one facility can expose them to new diseases, which reintroduced birds could spread to wild populations. A successful program also needs enough birds to ensure a robust gene poolāat least two or three pairs, although 20 or more is ideal.

Even if birds are bred successfully, releasing them is always a gamble: When Loro Parque set free the first captive ³§±č¾±³ęās Macaw in 1995, it survived about two months before flying into a power line. A review of 47 parrot-reintroduction events from the late 1970s through 2009 found that 45 percent of the time, the majority of released birds either died within a year or did not reproduce.

By the late 1990s reputable zoos emphasized their education role, funneling revenues toward field research and conservation. Jersey Zoo still touted its St. Lucia Parrots, but mostly funded in-country research. Loro Parque, whose logo features a ³§±č¾±³ęās Macaw, spent more than $600,000 on ³§±č¾±³ęās conservation programs in Brazil.

Private breeders still had many rare parrots, and George Amato, now head of conservation genetics at the American Museum of Natural History, wanted to preserve their genetic viability. When he contacted breeders, he got a rude awakening. āThey were almost deliberately not keeping accurate records,ā he says. āItās absolutely not conservation. Itās just a distraction to the real threats to these species.ā

By the turn of the century, breeders found their passion maligned by scientists and conservationists. International regulations sometimes put them at odds with the law and left them with a dwindling and often inbred supply of birds. Justifying their hobby meant propping up the old, fairy-tale version of captive breeding. But regulations had walled off the rare species they longed to propagateāat least until someone found a way to bring them together.

Fresh out of prison, Guth turned his talent for getting what he wanted to acquiring birds, a fixation he had never fully abandoned. He didnāt, at first, have any inclination to become a conservationist. He lived as a global nomad, a dealmaker who built his personal collection as his bird-hungry benefactors paid for his travel and hotel bills.

His entrĆ©e into the parrot worldās highest echelon began on July 23, 2005, when he swooped into Switzerland and bought his first three ³§±č¾±³ęās: Ferdinand, Richie, and Beauty Queen. That year the entire breeding population amounted to 54 birds distributed among 10 or so owners and descended from seven wild individuals, likely smuggled out of Brazil. Brazil had given up on legally compelling the birdsā return, but commercial trade of the species was still forbidden. Nobody thought theyād be allowed to cross international borders.

Parrot collecting can be a competitive sport, and Guth beat out a Qatari sheikh for the trio. āThe sheikh was pissed off,ā says Ryan Watson, who tended the sheikhās parrots. Guth got Germany to approve the import by vowing to cooperate with Brazil on breeding.

As word of Guthās coup spread, Claus Utoftāthe Ferrari-driving owner of a Danish clothing empireāproposed creating an association and building a German aviary. They founded ACTP in early 2006. Guth already had a good rapport with Irina Sprotte, the German official responsible for CITES permits, and later an ACTP consultant. Once birds were in Germany, they could freely move them to other E.U. countries. German authorities gave Guth contracts to care for confiscated parrots, including at least one St. Vincent Parrot. Guth scoured the world for more. At least 30 St. Vincentsāthe worldās largest private collectionāwere held in Florida by an aging clairvoyant named Ramon Noegel. Guth and Utoft bought them all. On October 17, 2006, Guth registered ACTP as a nonprofit in Florida. The next day he listed six St. Vincents on parrot4sale.com using the email address spixdeutschland@aol.com.

Guth figured it would be easy to get the birds out of Florida. But Timothy Van Norman, then the FWS permit chief, says ACTPās initial application raised eyebrows: āIf you are breeding for conservation purposes, Florida would be a more conducive climate than Germany.ā Equally troubling was the sketchy provenance documentation Guth had been given on the birds, which were said to predate CITES. Guth made a personal appeal to Van Norman in Virginia, but his first application was denied. Although ACTP and St. Vincent had signed a technical partnership for parrot conservation in 2006, Guth needed a breeding agreement to make a better case for exporting the birds. He donated chickens, fertilizer, and banana plants to the agriculture ministry. He also announced his intention to build a $406,000 wildlife conservation and education center, local media reported.

St. Vincent signed the breeding agreement, despite forestry officialsā misgivings. āItās our national symbol and should not be treated like a trading commodity,ā one emailed a colleague. āACTP presents no plans and have been asking us for a document that will show that we practically begged them to take and keep our birds,ā wrote another. Nevertheless, St. Vincent shipped 16 parrots to Germany, anticipating theyād be bred with the Florida birds. Van Norman was still troubled that the agreement allowed ACTP to own some of the progeny. But his supervisor, Roddy Gabel, overruled him. āWe had to trust that the other countries and people involved were operating in good faith,ā Gabel says. āThe Europeans in general have a more lax approach to regulating breeding facilities than we do.ā

Guth continued to build his parrot war chest. He inked a breeding agreement with St. Lucia, which requested that Jersey Zoo send its five parrots to ACTP. He also found unconventional funding sources. In 2014 a German tabloid published a photo of Guth getting into a Mercedes registered to Arafat Abou-Chaker, a Berlin crime family member and past ACTP donor. (Guth has said taking the donation was a mistake, and he hasnāt been implicated in any wrongdoing.)

His most vocal nemesis was Wolfgang Kiessling, the multimillionaire collector-turned-conservationist behind Loro Parque. They were both part of the ³§±č¾±³ęās Macaw Re-Introduction Project, a partnership of breeders, conservationists, and the Brazilian government coordinated by California-based Parrots International, created with an aim of reintroducing the birds to the wild.

Loro Parqueās ³§±č¾±³ęās legally belonged to Brazil. Kiessling signed over ownership during an earlier ³§±č¾±³ęās partnership in the 1990s, hoping other collectors would follow. None did. Nor did the partners permit Kiessling to buy a ³§±č¾±³ęās pair for exhibition, which would generate income to further fund efforts in Brazilāefforts Kiessling had already bankrolled. No ³§±č¾±³ęās were on display at the time, and the view was the precious individuals should be reserved for breeding.

Kiessling was displeased when Guth purchased his first three ³§±č¾±³ęās, making them a commercial object once again and disregarding a pact breeders had made. Shortly after, Guth told the consortium heād purchased 12 more in Switzerland; he refused to share DNA samples, leading those birds to be ejected from the breeding program in 2008. The two men butted heads until Kiessling finally left the group. Thatās when his magnanimous giveaway to the Brazilians came back to bite him. Brazil asked Loro Parque to send them four birds and Guth two others. Guth has since sent ³§±č¾±³ęās to be displayed at zoos in Singapore and Belgium in exchange for funding. Times had changed as ³§±č¾±³ęās numbers had grown. But not soon enough for Loro Parque, which never exhibited its prized species. Kiessling clung to his last ailing bird until her death in 2014. He didnāt even respond when Brazil requested the carcass.

Four months after I met Guth, he invited me to ACTPās $3.8 million zoo in Berlin. He picked me up at the airport in his BMW. Over dinner, he grumpily waved away my recorder and expressed annoyance at every question. The next morning, before visiting the zoo, he gave me a contract stipulating that I couldnāt quote ACTP employees or share photos without the boardās written approval. We wrangled over the wording and its meaning for hours. When he implied I could still quote him, I signedāa miscalculation that ultimately led to drawn-out negotiations over fact-checking and a cease-and-desist letter. The photographer, too, was sent a cease-and-desist letter and told that Guth had withdrawn consent for photography. Nervous about a lawsuit, and her personal safety, she asked ±¬ĮĻ¹«Éē not to publish her photos. Iāve chosen not to quote Guth from my interviews, to avoid any possibility of violating the contract or journalistic ethics.

But before all that, before the escalating legal actions, Guth took me and the photographer around the zoo. He seemed, finally, at ease. Bundled up in winter clothes, we walked around cages organized by geographyāAustralia, the Caribbean, and South Americaāand decorated with colorful murals depicting the birdsā native habitats. The facility struck me as impeccable. Pampered birds drink only bottled mineral water. Technicians weigh meals to the milligram.

Inside a nursery, Guth and I watched a technician pour organic oats into a bowl. With gloved hands, she retrieved a ³§±č¾±³ęās chick from an incubator and placed it atop the bed of grain to weigh it. A baby parrot is a homely creature with pink, wrinkly flesh, but I saw Guthās hard expression soften when this one came into view. The staffer squirted a warm syringe of food into its open beak, and it jackhammered its head to force down the gruel.

Most of the 150 ³§±č¾±³ęās at ACTP that dayāsome 90 percent of the global populationāwere originally bred in Qatar. Guthās one-time competitor, Sheikh Saud Bin Mohammed Bin Ali Al-Thani, reportedly injected millions into that effort, including developing an artificial-insemination program, and then ran out of cash. Three years after his untimely death, in 2014, ACTP expanded its aviaries and was loaned all of his ³§±č¾±³ęās and ³¢±š²¹°łās Macaws for five years. āThe best thing that happened to the ³§±č¾±³ęās Macaws was the sheikh dying,ā says Watson. He doubts the sheikh would have returned the birds to Brazil and has come to respect Guthās devotion to his mission.

Guth also impressed Mark Stafford, founder of Parrots International, when, in 2006, he helped pay for a farm with the last known ³§±č¾±³ęās breeding site. For years Guth remained reserved as the newcomer at meetings for the reintroduction project. But by 2015 Kiessling was out and the sheikh was dead and Guth had lost patience with the expertsā yammering. At a meeting in Campo Grande, he told everyone to leave the room except those who had cash to carry out their plans. āMartin is a no-bullshit kind of guy,ā says Stafford. āHe can be nice and he can beāāhe pausedāānot nice, I guess.ā

The reintroduction site consists of a large protected area of Caatinga forest that allows ranching but is off-limits to development. ³§±č¾±³ęās are dependent on riparian corridors, where they nest in tree cavities. With habitat secured, Brazilian NGOs and wildlife authorities are planning how to ease the eventual return, such as by controlling beehives in tree cavities. Determined to avoid the fate of the first failed reintroduction, the Brazilians āhave done quite a bit to help improve the chances of success,ā says FWSās White, a project consultant.

At the core of the protected area sits 6,000 acres of privately owned land, where ACTP is building breeding and reintroduction facilities. Its role in Brazil is limited to managing birds there until their release, which will be staggered over the next five years. Cromwell Purchase, who led Sheikh Saudās ³§±č¾±³ęās program and is ACTPās scientific director, has moved to Brazil to work on the first test releases, expected this year. Guth aims to keep approximately 30 ³§±č¾±³ęās pairs in Berlin, as breeders must ship 70 percent of chicks to Brazil each year. That mandate, combined with ACTPās delivery of 52 ³§±č¾±³ęās to Brazil in March, leaves Guth with empty cages to fill.

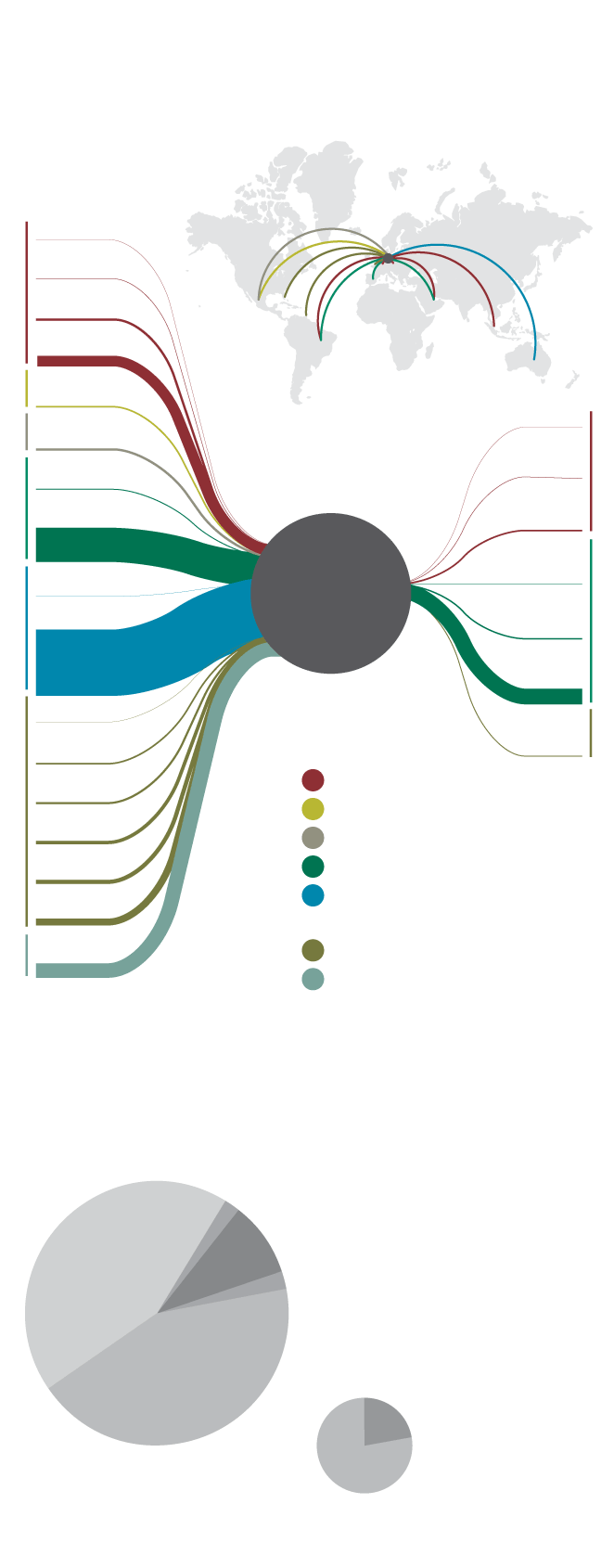

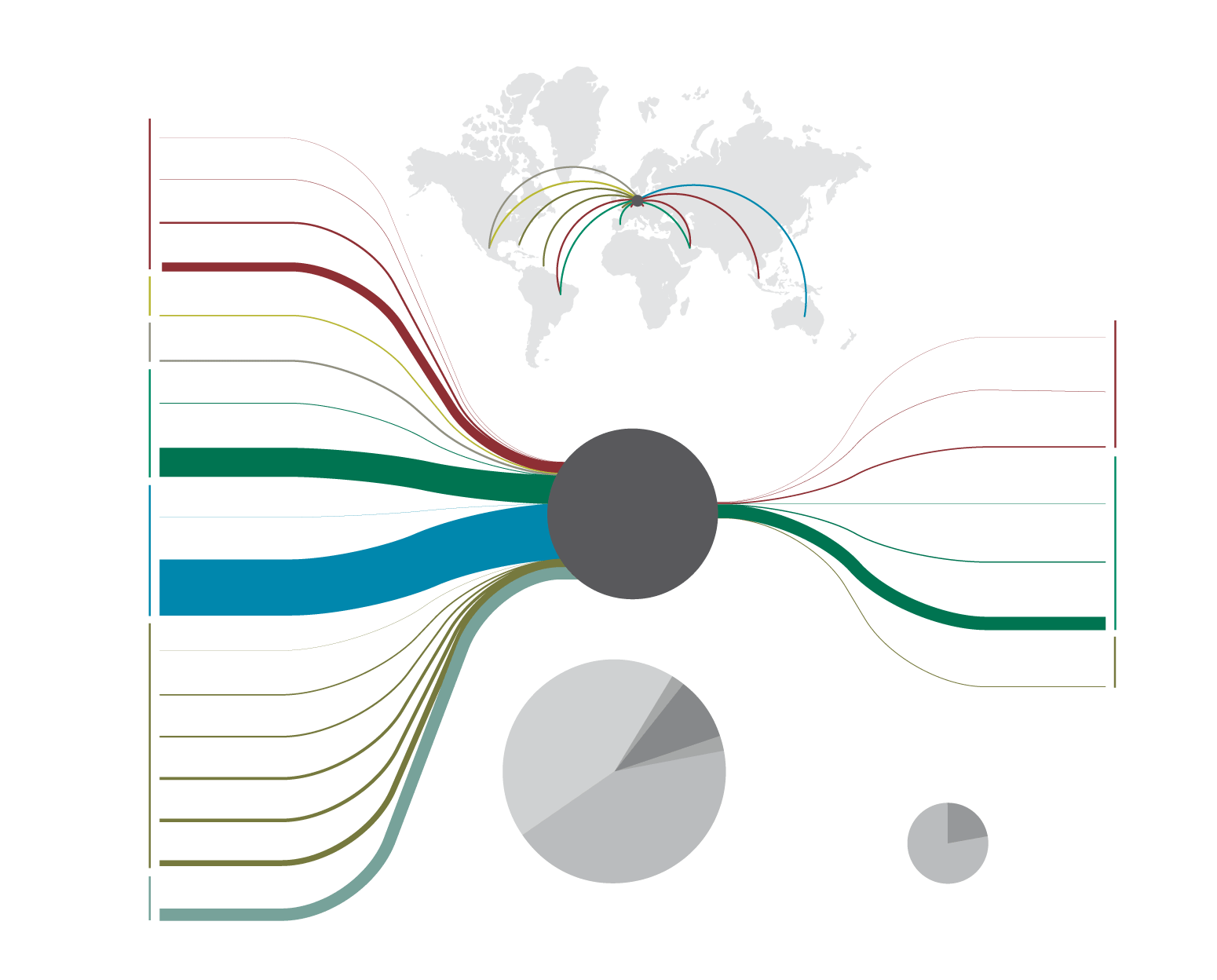

Birds Sent to ACTP vs. Birds Leaving ACTP

Source country/

(number of birds)

Czech Republic (1)

Brazil (2)

Germany (8)

Qatar (37)

Mexico (6)

Czech Republic (1)

Mexico (8)

Singapore (2)

Spain (3)

Qatar (120)

Belgium (6)

Association for

Singapore (2)

the Conservation

Germany (1)

of Threatened

Australia (232)

Parrots (ACTP)

Belgium (5)

Brazil (55)

Germany (1)

St.

Vincent (3)

Species

St. Lucia (6)

Jersey Island,

UK (7)

³¢±š²¹°łās Macaw

Maroon-fronted Parrot

Thick-billed Parrot

³§±č¾±³ęās Macaw

Cockatoos, lorikeets, and other parrots

Caribbean parrots

Additional species

Dominica (12)

St. Vincent (15)

Florida (24)

Multiple (51)

Source of birds sent to ACTP vs. destination of birds leaving ACTP

Source

Foreign collectors (232)

Foreign zoos (10)

Range country (49)

European conļ¬scation (11)

Australian breeders (232)

Destination

Foreign zoos (16)

Repatriated (56)

Birds Sent to ACTP

Species

Source country (number of birds)

³¢±š²¹°łās

Czech Republic (1)

Macaw

Brazil (2)

Germany (8)

Birds Leaving ACTP

Qatar (37)

Maroon-fronted

Parrot

Destination

Species

Mexico (6)

Learās

Czech Republic (1)

Thick-billed

Macaw

Parrot

Mexico (8)

Singapore (2)

³§±č¾±³ęās

Spain (3)

Macaw

Belgium (6)

Qatar (120)

Spi³ęās

Association for

Macaw

Singapore (2)

Cockatoos,

Germany (1)

the Conservation

lorikeets, and

of Threatened

other parrots

Australia (232)

Parrots (ACTP)

Belgium (5)

Brazil (55)

Caribbean

Germany (1)

Foreign collectors (232)

parrots

Carribean

St. Vincent (3)

Foreign zoos (10)

parrots

St. Lucia (6)

Range country (49)

(7)

Jersey Island, UK

European conļ¬scation (11)

Dominica (12)

Australian breeders (232)

St. Vincent (15)

Foreign zoos (16)

Florida (24)

Repatriated (56)

Multiple (51)

Additional

Source of birds

Destination of birds

species

sent to ACTP

leaving ACTP

In an export application, ACTP once wrote that it āwill develop and apply novel methods for the funding of parrot conservation under the principle of āCan Wildlife Pay for Itself.āāāā ACTP certainly seems to have fine-tuned a model in which parrot breeding funds its operation. In 2014 Germany granted it a zoo license, giving it a tax exemption, among other benefits. Thanks to that newfound status, it could also take advantage of a loophole in Australiaās export ban that allows exports for exhibition purposes. ACTP has since obtained more than 200 parrots from Australia. Guth and his members are breeding them in Europe, though most have odd color mutations, making them valuable only for the allure and cash flow they potentially generate.

Whether or not ACTP will meaningfully advance parrot conservation, especially for the breathtaking range of species it has acquired, remains an open question. Nine years after its breeding agreement with St. Vincent, the wildlife center hasnāt been built, and Guth just repatriated the first three chicks in November. St. Vincentās forestry head was unaware that ACTP has hatched 10 chicks since 2016. St. Lucia, meanwhile, has gone all-in, plucking wild chicks from nests for ACTPās breeding program. ACTP, in turn, has reportedly provided $2.5 million to revamp a zoo there.

As for Dominica, Durand says he was asked to take temporary leave for speaking out against ACTP, and in-country parrot work has ground to a halt. āThey have almost demolished our conservation program,ā he says. āThat is what ACTP has done.ā

On my second morning in Berlin, Guth led me to the two Imperials shipped from Dominica. We saw the male immediately, a dark form at the far end of the cage. When he spotted us, he slipped into the heated back room, where Guth said his much older mate was huddled. Fewer than 50 Imperials likely remain in the wild. Females probably take 10 years to reach sexual maturity and typically lay one egg per year, making a self-sustaining population a farfetched undertaking.

ACTP has said Dominica, worried about more storms like Maria, instigated the transfer of its parrots. The 10 Jacos brought over had already produced two chicks. The Imperials, none. When I asked Guth what he could achieve with just two, he reminded me that ACTP began with three ³§±č¾±³ęās.

I knew by now a plan was likely already taking shape. Reillo, who led the call for the Jacosā return, isnāt only one of Guthās fiercest opponents. He also tends to the only other known captive Imperial Parrot, evacuated due to an emergency in 2010. At the 2018 CITES meeting in Germany, Guth or his people are rumored to have approached U.S. officials about exporting the Imperial in Reilloās care to Germany. It could only happen with Dominicaās endorsement, of course.

This story originally ran in the Summer 2020 issue. To receive our print magazine, become a member by .